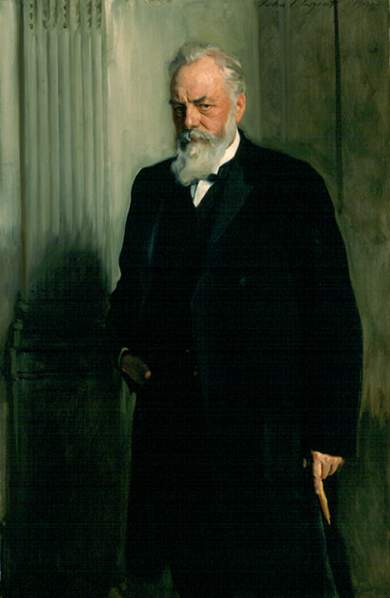

John Fyfe (1830 – 1903)

John Fyfe took over his father’s business at the age of 16 and within eight years he was sending more granite out of Aberdeenshire than any other company in the trade.

Kemnay was virtually created by a railway and subsequently became the scene for celebrated developments in yet another major North-east industry, which was granite quarrying and working. It is not quite true to say that the railway created the Kemnay granite industry or Kemnay itself. A settlement did exist in the early 19th century, clustered around Kemnay House, the Kirk and the Parish School, which had more than local reputation. It was little more than a Clachan, however.

Similarly, granite had been quarried on a small scale in the district for some years. In 1830 The Laird Burnett of Kemnay took stone from Paradise Hill for extensions to his mansion Kemnay House. However, the scale of both the settlement and the granite industry expanded greatly in the late 1850’s as a result of railway politics.

The Great North of Scotland Railway (GNoSR), always defended its Aberdeenshire monopoly with vigour. When the Railway’s directors discovered that the Deeside, then a separate and hostile company, were planning a line from Drum, through Echt to Alford they moved quickly to revive an earlier suggestion of a branch from to GNoSR main line at Kintore that would pass through Kemnay and Monymusk to Alford. The Alford Valley Railway was authorised by Parliament in 1856 and opened in March 1859. Always the creature of the GNoSR, it was absorbed into that company in 1866.

Two men realised the potential generated by the Alford Valley Railway in Kemnay. The first was a 28 year old entrepreneur called John Fyfe. In 1858, while the railway was being built, he took a lease of the Paradise Hill quarry, which was very handily placed for the railway. Other quarries sprang up along the new line at Tom’s Forest, Correnie and Tillyfourie – the last being the North-east centre for making kerbstones and all eventually fell into John Fyfe’s hands. The quarry flourished and as the demand for granite increased, so did the demand for workers, so he built four tenement blocks to house them.

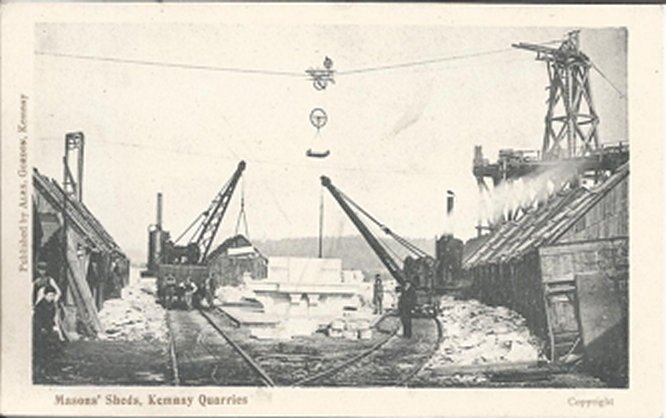

Kemnay Quarry became famous for more than the quality of its stone. Quarrying was very primitive when Fyfe arrived at Kemnay, but he introduced some major advances. He always sort technical improvements in granite working and many innovations that later became commonplace were pioneered at Kemnay. He met a young engineer called Andrew Barclay of Kilmarnock who was developing a steam derrick crane and together they produced the Scottish steam derrick, which revolutionised the business by allowing them to quarry downwards for better stone rather than just into the hill.

A few years later he applied a notion he had got from watching a postman pass a bag of mail across the Dee at Abergeldie by means of an endless rope. He fitted a travelling carriage to an endless rope and created the steam powered Blondin. Named after the famous-high wire artist then at the height of his fame. Fyfe’s Blondin became standard equipment in the world’s quarries for lifting stone from the bottom of the dip to the loading bank.

Kemnay Quarry, Blondin, Mason sheds and railway lines

In 1872 he scored another first when he superceded the primitive and dangerous practice of shot-firing by fuses. He pioneered electrical shot-firing, not only was this safer, it also allowed much larger scale extraction from the quarry. On one occasion, 70,000 tons of granite was blasted from Paradise Hill in one operation. Loaded on a single train, the worked granite from this explosion would fill 9,000 trucks and occupy 30 miles of track. One sees how central the Alford Valley Railway was to John Fyfe’s plans.

The quarry flourished and as the demand for granite increased, so did the demand for workers, so he built four tenement blocks to house them. By 1880, 250 men were employed with 7 steam cranes and 2 Blondins. Blocks of granite 30ft long and 100 tonnes in weight were produced in its heyday. Celebrated for supplying granite for the Holborn Viaduct. It was opened in 1830 by John Fyfe, and became fully commercial in 1858.

Aberdeen’s most famous quarry is at Rubislaw, which is Europe’s largest man-made hole but Kemnay quarry has provided the stone for many of the city’s most striking buildings. After providing the granite for the Town House in Aberdeen, Fyfe’s supplied the same stone for many other buildings in the city, including the Salvation Army citadel in the Castlegate, the Caledonian Hotel, His Majesty’s Theatre, Queen’s Cross and Beechgrove Churches, but the most spectacular of all was Marischal College, the second largest granite building in the world after the Escorial in Spain. The Marischal College building is now the HQ for Aberdeen City Council.

By the turn of the century, Kemnay was thriving and as well as the village’s grey granite, Fyfe was sending pink Corrennie granite all over the country. Kemnay reigned supreme, partly as a result of the stone’s nature (it is easily worked for granite), and its glorious pearly silver white colour made it extremely popular for prestige construction and monumental work. Kemnay granite provided the foundations for the Forth and Tay bridges, the Liver Building in Liverpool, numerous bank headquarters in London, several London bridges, including the Tower, Blackfriars, Southwark, Vauxhall, Kew and Putney, and the Queen Victoria memorial opposite Buckingham Palace was built in the sparkling stone. More recently it has been used for the construction of the Scottish Parliament in Edinburgh.

As stated earlier, two men realised the opportunities that the railway presented in Kemnay, the other was the local Laird. In January 1860, two years after Fyfe had taken his lease on Paradise Hill and ten months after the railway had opened, the Aberdeen Free Press advertised that: “Mr Burnett of Kemnay has resolved to lay off for feuing and building purposes, about ten acres of ground, in the vicinity of the Station at Kemnay. The situation is both convenient and attractive; besides the faculties of communication which the railway now affords, the ground is in the near neighbourhood of the Parish School, Post Office, etc. It commands a pleasant view of the River Don, and of the surrounding scenery”.

The land was carefully zoned. One section was to see the construction of “Houses for the Railway Servants” and a small Hiring Establishment and Lodging House. Two sections would be given over to village tradesmen, and a third to labourer’s houses. The last section was reserved for “small Villas”. It is this section, around Kendal Road, that gives Kemnay its curious character as a rural clone of Aberdeen’s West End.

Kemnay quarry is still worked but ownership passed from John Fyfe Ltd. To Bardon Aggregates and is presently (2014), owned and operated by Breedon Aggregates who supply Fyfestone precast reconstituted stone products and aggregates to the building industry.

The Alford Valley Railway has gone, the first Kemnay Station is now occupied by a Co-op mini-market and the second Kemnay Station site is now occupied by Council houses and old people’s bungalows and yet that railway made Kemnay and its famous quarry. However, Kemnay has evolved and adapted over the years and is now a thriving village. Kemnay has expanded and continues to expand due to housing demand as a result of the North Sea oil boom. There are still some local jobs at Kemnay Quarry but the majority of residents commute to Aberdeen or Inverurie for employment.

Burnetts of Kemnay

Kemnay Quarry

Kemnay Railway

Acknowledgements and Sources of Information

Doric Columns

Ian Carter, Senior Lecturer in Sociology at Aberdeen University

Evening Express on 05 July 1980,